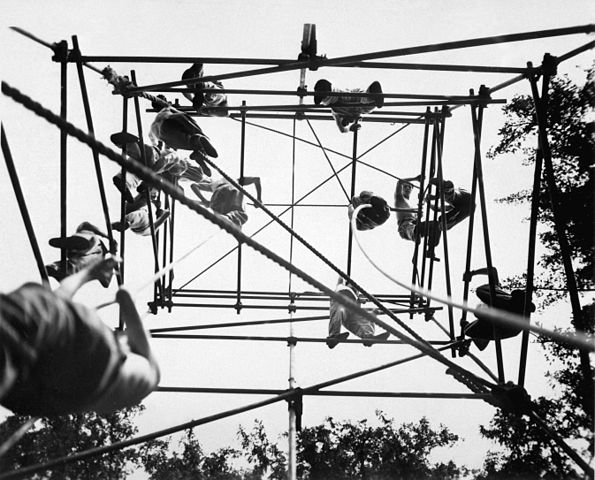

By US Office of Strategic Services - Public Domain. Special operations training on high bars in obstacle course in Milton Hall, England.

There is a show on Netflix called Churchill’s Secret Agents: The New Recruits. The reality show takes people from today and puts them through the Special Operatives Executive (SOE) training implemented by the British during WWII. Imagine pulling on your itchy wool socks and heavy felted uniform to master the art of using a hair pin to pick a lock, learning how to plant an explosive in a dead rat, or deciphering secret codes from staticky radio transmissions.

Turns out, that is probably the easy part of the job. John Braddock writes in A Spy’s Guide to Strategy:

“When you’re a spy, you see a lot of strategies.

You see the grand strategies. The worldwide strategies. The strategies of transnational movements. The strategies of global influence networks. Across space and time.

Then you zoom in. To one continent. To one time. Where nations collide. Where resources matter. Where histories matter. Where plans for revenge and restitution and glory become strategies.

Then you zoom in again. Within a nation. To factions. Political parties. You see groups teaming up with other groups to pursue revolution and reward and independence.

Then you zoom in on an individual. A person. Someone with dreams. And fears. And anger. And love. Someone building strategies to satisfy them all.”

While we aren’t training to become spies (well, most of us anyway), many of us bump into strategy in our work or volunteer engagements. We are thrown into strategic sessions, we hire strategic consultants, and we write strategic plans. There are thousands and thousands of books, podcasts and blogs on strategy.

However, there seems to be a mystery around strategy. If only we could craft that one amazing strategy, we would have it all figured out. Unfortunately, that’s just not how it works.

Strategic thinking seems mystical because isn’t something that most of us do at any kind of depth. The time we spend on strategic planning is often minimal and the thinking we bring to it just skims the surface. In most situations, the requirements for doing strategy are minimal.

In one strategic planning session I was involved in, a participant asked “am I even qualified to do this?” after which the team replied “of course!” without pausing to think about what would be required of someone to do strategic thinking.

In a conventional setting, it seems that we are qualified to do strategy if we:

- Are aware of the higher level purpose of the authorities (board, CEO, etc.) and can work within those boundaries

- Will support social-cohesion by “being part of the team”

- Can work with given information (often a brief summary of the situation and issue)

- Can work within the timeline (plan for the next 5 years in less than 5 hours).

But what if the situation requires something more? What if the authorities have formed a vision that undermines community or life systems? What if the team doesn’t have the right mix of capacities? What if the information is untrustworthy or inaccurate? What if the situation is emerging and it will take ongoing work to understand?

Because most of our situations don’t require it, we don’t even seem to recognize that there might be deeper levels of understanding that help us develop better strategic thinking. But when you look across the historical record and across fields of endeavour, especially in situations where the stakes are high, you begin to find examples people and groups who have developed deeper, adaptive understanding of strategy.

By studying examples like the SOE training, we can find rich examples of how we can develop adaptive strategic thinking that we can apply to our own life engagements. This kind of thinking is required of us to navigate the complex, emergent challenges that face us as a species in the twenty-first century.

What is strategy?

Simply put, strategy is developing a clear sense of what’s going on and what to do about it. While that sounds easy, there are all kinds of ways that this can go wrong. Ignorance and error can be introduced both in what we think is going on and what we think we should do about it.

In our daily engagements, we know that strategy is valuable, we’ve flagged it as an important capacity but, as we’ve already found out, we don’t often go very far beyond that. We do the strategic plan, check the box and move on to the rest of our everydayism. The inquiry stops.

When we make attempts to go a little deeper, we often only go to a level of representational understanding. You may know the parable of the blind men and the elephant: a group of blind men come across an elephant and, in trying to figure out what it is, they each feel different parts of it. One man feels the trunk and claims it is a snake, one feels the leg and says it is a tree, and another feels the tusk and claims it is a spear. The parable is used to explain that humans have limited perceptions upon which they may claim truth and can turn out to be wrong.

This parable also tells us something about the limitations of representational understanding. While they may eventually put all the components together and figure out it is an elephant, the representational understanding doesn’t tell you much about its function. It doesn’t help the blind men to understand the natural history of the elephant, how it evolved, or what role it plays in the habitat. This would require a different kind of inquiry to understand.

We carry a representational understanding of strategy too. We know that strategy involves components, like purpose, objectives, and tactics. But this level of understanding can fool us into thinking that we have it all figured out.

A meteorologist doesn’t just list the weather elements like wind, rain, sun, and clouds; they try to make predictions based on functional understanding of how these elements behave. They look for significant patterns and use historical data to draw insights about what could happen. While they don’t always get it right, the sophistication of intelligence gathering has increased over the years and their accuracy has improved.

I once toured the National Weather Centre in Oklahoma, which is home of the Oklahoma Mesonet – a network of 121 weather stations monitoring for thunderstorms, tornadoes and other severe weather events across the state. The Oklahoma Mesonet was created after a 1984 flood that killed 14 people. Emergency personnel recognized that they couldn’t get accurate data quickly enough to manage the situation. Now, the National Weather Centre houses floors of meteorologists and computers monitoring, sensing and detecting data to run sophisticated analysis and create prediction models that serve to inform the public and prevent harm to human lives.

The meteorologists are, in fact, using strategic thinking. Strategy involves developing an accurate sense of the situation and being able to identify the most significant parts that have created the situation and what will influence it as it unfolds. It is also about identifying significant errors that could be made and how to avoid them.

Good strategists develop the skill to be their own B.S. detector. We need only look to the current United States presidency to see how a lack of this strategic capacity impacts Trump’s decision making.

In The Assault on Intelligence: American National Security in an Age of Lies, Michael Hayden (retired United States Air Force four-star general and former Director of the National Security Agency, Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence, and Director of the Central Intelligence Agency) explores the concept of metacognition and what happens when this capacity is missing. Hayden refers to a 1999 study by Justin Kruger and David Dunning published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology which explained that:

“People tend to hold overly favourable views of their abilities in many social and intellectual domains. The authors suggest that this overestimation occurs, in part, because people who are unskilled in these domains suffer a dual burden: Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the metacognitive ability to realize it.”

Good strategists recognize that we are always more ignorant than we are wise. There is always more that can be known in order to create a more accurate picture of what is going. There are always more capacities that can be developed to expand what you can do in the situation. Searching for blind spots and ignorance in our own thinking and in the thinking of others pushes us into deeper adaptive levels of strategic thinking.

The Function of Strategy

To start to explore those deeper levels, it helps to think through the function of strategy. What does a strategy do for us? It certainly doesn’t guarantee success. As Mike Tyson put it “Everyone has a plan ’til they get punched in the mouth.” Von Moltke, Field Commander in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, said that “no plan survived contact with the enemy.” Lawrence Freedman in Strategy: A History writes “while strategy is a good thing to have, it is also a hard thing to get right. The world of strategy is full of disappointment and frustration, of means not working and ends not reached.”

But President Dwight D. Eisenhower added some important nuance to this when he said in a 1957 speech that “plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” In other words, the process of planning is so much more important than the output. It is in that planning that we are gathering intelligence, learning about ourselves and the enemy, building capacities and preparing ourselves for whatever might come our way.

We should expect that plans fail because outcomes are contingent on so much more than the stated plans and objectives. They are a result of moment to moment decision making of the players involved and the circumstances in which they are embedded. In other words, strategy supports adaptive positioning in situations of uncertainty with unreliable allies and intelligent adversaries.

Whether it is in the board room, on the battle field, or in any situation, there are 3 ways that we adapt:

1) retroactive adaptation;

2) real-time adaptation; and

3) anticipatory adaptation (or strategic foresight).

Retroactive adaptation involves creating a new pattern based on what has happened in the past. Real-time adaptation allows us to adapt based on what is happening right now. Lawrence Freedman describes an example of this in Strategy: A History. “Before 1800, intelligence-gathering and communication systems were slow and unreliable. For that reason, generals had to be on the front line – or at least not too far behind – in order to adjust quickly to the changing fortunes of battle. They dared not develop plans of any complexity.” Improvements in communication capacities helped the generals move from retroactive to real-time adaptation.

Anticipatory adaptation gives us strategic foresight which is a big leap in adaptive power and the ability to manage complexity. It is anticipatory thinking which allows us to predict what might happen and what the potential threats and opportunities might be.

To anticipate, one needs to understand the enemy. In the example of the Oklahoma Mesonet, the adversary is the complex, emergent phenomenon of weather. When we are dealing with intelligent adversaries and unreliable allies the principle is the same.

In The Art of War, Sun Tzu states:

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

Our conventional approaches to strategy don’t dig into the sources of uncertainty and the paths of development of our adversaries are on. They don’t tell you how the enemy is learning, how they are making sense of the situation, what capacities they hold and how they form their intentions.

In A Spy’s Guide to Strategy, Braddock proposes that the powers that be in the United States didn’t have a good understanding of Osama Bin Laden’s meaning making and intentions. Early on, they believed (or at least they led the public to believe) that it was a simple story of Bin Laden vs. the United States. As Bush said in Congress on September 20, 2001 “They hate our freedom.”

But Bin Laden’s real goals were to create a Caliphate and for him to become Caliph. Bin Laden wanted to position himself as the leader of the Arabic community by removing United States’ influence in the Middle East and creating allies with the leaders of Muslim countries to position himself as the Caliph.

Braddock proposes that the 9/11 attack was not just about attacking the west but was a version of a tactic used by leaders throughout history to “do extraordinary things.” Bin Laden may have believed that the 9/11 attack better positioned him to become the leader of the Caliphate – his ultimate goal.

Missing this understanding, the U.S. had a hard time making predictions about what Bin Laden might do next. They kept anticipating another attack on American soil. Home security increased, but it is possible that Bin Laden had no intention of another American attack post 9/11.

This example shows how hard it is to understand and anticipate the adversary. When you think of all of the people working on gathering intelligence, scoping out different players, analyzing reports for accuracy and finally making decisions on what to do, it clear that the situation is incredibly complex.

Strategy and Complexity

Good strategists dig into complexity and help others to understand it. The art of strategy is an ability to look for promising paths in complex situations. This is at the core of navigating solution space.

Our conventional training and education doesn’t prepare us well for managing complexity. Most of the challenges we face are fairly predictable in nature and we can draw on established procedures to overcome them. If I get a flat tire on a busy road, I know that there are safety protocols like my flashers that help protect me from harm, and I have a manual to follow in order to get myself out of the situation. Or perhaps I don’t have a clue, so I call Alberta Motors Association and they send someone who knows the procedure.

Challenges that are unpredictable, complex and emergent are the ones that we aren’t equipped to deal with well. Add in the unpredictable and adaptively resistant nature of adversaries and we are no longer in a situation that most of us are used to. To become good strategists, we need to cultivate our comfort for complexity and start to build the skills for systemic adaptive understanding.

As we discussed already, a system is not just about the components that make it up. There is plenty of insight in the interconnections, relationships and dynamics of the system. As Donella Meadows in Thinking In Systems: A Primer said “You think that because you understand ‘one’ that you must therefore understand ‘two’ because one and one make two. But you forget that you must also understand ‘and.’”

Good strategic thinking should have you sorting through the system in which the players are embedded but also the systems within other systems. What systems are the adversary using? What technologies, or organizational methods do they have? And how does it all integrate together?

In a military context, take for example the enemy’s weapon system. What artillery capacity do they possess? What is the strength of that artillery? What does it take to make the artillery? What resources are they relying on? What is their logistics system to acquire those resources?

Good strategic thinking should also alert us that once we learn something, it is likely our enemy has already learned it or will soon learn it too. Strategy is never about position; it is about positioning. The field is always shifting and changing and it is why strategies should never be static.

It is not just about understanding the systems in which the action is embedded, it is about developing a systemic approach to understanding. What are all the different means we can use to understand what is going on, what we could do about it and what our adversaries might do about it?

Another way to define strategy is that it is “venturing intelligence,” which implies understanding the most significant aspects of how have things come to be and how could they unfold. It is part of developing an orienting story that explains the situation, the challenges may be faced and what the group may need to do. Stories create a cohesiveness to the group and are an important part of an adaptive, integrated strategy.

Not everyone involved needs to know all the details. As Ken Low, Human Learning Ecologist with the Human Venture Institute puts it, “The difference between a successful General and an unsuccessful General is the ability to articulate the situation in a compelling way with the right amount of complexity.”

Strategy and Frames of Action

Systems are inherently nested and hierarchical. Military commanders have long recognized how helpful it is to distinguish the frames of tactics, operations, strategy and grand strategy (grand strategy is the national policy and long-term objectives). But this hierarchical structure can be found in all situations; for example, religions provide high-level, transcendent frames that inform daily tactics on how to go about living.

One of the problems with a surface level understanding of strategy is that it is easy to delude yourself that you have a strategy when all you have is tactics. Humans have a bias towards operations and tactics. We tend to jump to action on what is right in front of us. We aren’t as good at developing higher level purposes.

Strategy links tactics to a higher level purpose, or transcendent frame. Whether we are conscious of it or not, we all have transcendent frames that tell us what life is all about. As individuals, organizations, communities, and society, we all carry them, but rarely do we examine them. The unexamined transcendent frame is highly influenced by our socio-cultural context and socialization.

In today’s western society, our transcendent purpose is wrapped up in consumerism, affluence and contributing to growth of the economy. We have created a culture that celebrates individualism to an extreme, rewards celebrity and keeps us distracted by staring into our devices earning dopamine hits from views and likes.

This plays out, not only in our personal lives but in the global context too. Andrew Bacevich’s America’s War for the Greater Middle East: A Military History provides a good case study. He says, “From the outset, America’s War for the Greater Middle East was a war to preserve the American way of life, rooted in a specific understanding of freedom and requiring an abundance of cheap energy.”

With this as the higher purpose, strategies in the Middle East have supported perpetual war, increasing instability in the region and the rise of extremism. While some may be led to believe that the mission is to bring prosperity, democracy and peace to the region, year after year, Bacevich lays out how the Americans keep the conflict going in order to serve the purpose of maintaining their way of life.

The challenge of our time is that we haven’t figured out how to develop strategies that support thorough examinations of the transcendent values we hold. They don’t help us to ask: is this really what life is all about? What will happen when we realize that this way of thinking and acting is the cause of our ecological and cultural degradation?

It is hard to do course correction without strategy and, arguably, this is one of the most important reasons we need be studying strategy at a much deeper level. We can’t change our ways of living broadly without a thorough examination of our transcendent ideals and well developed strategic capacities to inform our actions and habits. We need strategies to live and learn by. We need a strategy for strategy.

For the sake of our species, we desperately need to learn how to set priorities and create strategies that reduce harm, waste, suffering, and injustice in our world and supports resourceful, resilient, responsible, wise human beings. We need to challenge our organizations and institutions to better understand the function of strategy and how it can link our everyday tactics with our highest ideals for humanity and for the planet.

It is not enough to care, or just to talk about it, we need to be working on developing an adaptively significant picture of what’s going on and what should be done and what should be learned. We need to be practicing strategic foresight for the future our species.

Strategy and Capacity Construction

This definitely sounds like a daunting challenge facing us but we need to recognize that it is not impossible to take on. Humans are an intelligent species that have figured out complex challenges before. Ken Low, summarizes that “the problem isn’t so much that we need to better understand strategy, it is that we need to better understand understanding.”

One of the barriers to learning is that what we can do at any one point is highly contingent on our past experience. If we haven’t had any reason to challenge our purpose and ideals, then it is difficult for us to test them. We just go along with what our culture tells us. Without strategy, we are driven by our lower level drivers, like greed and status, and as Low says “We don’t have our beliefs, our beliefs have us.”

Strategy is a type of adaptive learning that we can train for. It takes ongoing situational analysis, searching for sources of uncertainty and ignorance and identifying potential ventures or paths that could unfold. It is about assessing the promisingness of different plans and preparing oneself and the collective with the capacities needed to take that path.

Developing strategic thinking is a journey and there are a constellation of adaptive capacities needed to be able to do strategy well:

- Intelligence gathering

- Sensing, detecting, anticipating, preventing

- Assessment of significance

- Testing for accuracy and truth

- Diagnosis and design

- Striving and persistence

- Communication and story telling

Isaiah Berlin, philosopher, described that the great political figures could “understand the character of a particular movement, of a particular individual, of a unique state of affairs, of a unique atmosphere, of some particular combination of economic, political, personal factors. “ Freedman in Strategy: A History elaborates “This grasp of the interplay of human beings and interpersonal forces, sense of the specific over the general and capacity to anticipate the consequential “tremors” of action involves a special sort of judgment.” It is the development of this wise judgment that we need to understand and master.

Resources on Strategy

This is by no means a comprehensive exploration but I hope it provides you with some trailheads to explore. Understanding strategy is a mastery journey in adaptive learning.

Strategy is something that is almost universally misunderstood. There are pockets of adaptive explorations into strategy, especially in warfare, but good quality resources are hard to find. For example, there are tens of thousands of books on the civil war but just a handful on the strategy of the civil war.

Here are some resources on strategy that we recommend:

A History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides

Strategy: A History by Lawrence Freedman

The Future of Strategy by Colin S. Gray

A Spy’s Guide to Strategy by John Braddock

Thinking in Systems: A Primer by Donella Meadows

Strategy: Context and Adaptation from Archidamus to Airpower by Richard Bailey

The Art of Guerrilla Warfare by Colin M.G. Gubbins

Issues in Strategic Thought – From Clausewitz to Al-Qaida Naval Postgraduate School

More on War by Martin van Creveld

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121-1134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

HV Meta Framework Map 11: Adaptive Position and Positioning Dynamics

HV Meta Framework Map 69.1: Frames of Action

HV Meta Framework Map 70: Strategic Framing

HV Meta Framework Map 70.1: Strategic Planning and Integrative Dynamics

HV Meta Framework Map 75: Notes on Frames of Action

HV Meta Framework Map 101.3 : Challenge / Barrier Characteristics

This article is a summary from conversations and workshops of Human Venture Leadership. Much of the thinking came from Ken Low, who led this exploration into strategy, and members of the Human Venture Associate program who were part of the discussions. Thank you to Anna-Marie Ashton, Kim Rowe, Sami Berger and Natalie Muyres for input and review of this article.