It is 8:30 am when I roll my sleepy self out of bed. Sorry people, I have yet to figure out this whole waking up early part of adulting. I get in my grubby clothes, jump in the car and drive out to our farm just outside of town. Feed the chickens, look for eggs, look out in the field to see if the cows are still there. Yep, on to the next thing. I rush home, make some tea and sit down to my off-farm job. I fall down the rabbit hole of emails for a while…a long while. I work on some project budgets, think about who I should approach next for program funding, negotiate with a speaker about an upcoming event and sit through a staff meeting. I make some quick supper, do evening chores at the farm, sink into exhaustion and then do it all over again the next day. And on and on and on…

Welcome to my everydayism.

Maybe hearing someone else’s everydayism is a bit like seeing greener pastures, but I’m sure some of you have similar feelings as I do around your daily habits. How am I ever going to get out of this routine and get on with the learning and the work that I really want to be doing? (Although who am I kidding, I’m not giving up my chicken routine.)

What if we flipped this whole everydayism thing on its head? We all have life engagements that consume us, but what if we could use everydayism to our advantage and construct habits that feed meaningful lifelong learning that contributes to our human story? What if we could use it as a tool to help integrate our everyday engagements with the work that humanity and our planet need most?

Everydayism describes our daily habits and routines that are shaped by our priorities, values, beliefs, decisions, and responsibilities. And these, in turn, are shaped by the priorities of the communities, organizations and the socio-cultural systems in which we live. Some of these influences we are consciously aware of but much it we are not. What’s more, some of it, like our values, we can directly shape but much of it we cannot, like our culture. All of this makes everydayism something of a challenge to redesign.

Two years ago, I sat down and wrote a list of things that pull me away from the kind of learning and work I want to be doing and things that pull me towards it. Here’s what I came up with.

Things that pull me away:

- Contracts (I am self-employed) that are too specialized and narrow in scope: graphic design, website development, branding, etc.

- Email and social media

- Daily organizational and operational management tasks

- Family, friends (beers on Friday can maybe go either way)

Things that pull me toward:

- Contracts with real life challenges and questions: my most recent contract is about growing the next generation of ecological farmers

- Being in nature, observing and working with life systems (yay chickens!)

- Being with a community that feeds my soul (including the Human Venture community)

- Learning, reading and teaching

What I reflected on, after writing all of this, is that both lists can be approached with either conventional or adaptive thinking and learning and this goes on to shape our everydayism. What is the difference? Conventional approaches keep us trapped within the processes and priorities of the community and organizations we live and work in. The challenge of conventional learning is that it doesn’t orient us to potential blind spots or traps in our thinking. For example, I could be in the habit of only learning what I am told to learn by my manager. What are her priorities? What are the institutional priorities? This could lead to me into implementing things that don’t fit with what’s really going on or things that do harm without me knowing.

Adaptive approaches allows us move beyond this. In contrast to conventional learning, where we are motivated by acceptance and approval, adaptive learning is motivated by digging beyond surface level understanding and identifying ignorance and error in our thinking. We ask ourselves: what’s really going on? How things could unfold? How can we prepare ourselves to take on the challenges that lie ahead?

For example, looking back on my lists, I ask myself: what could I learn about organizational development that would support others to do adaptive learning. In fact, I’ve been on a path to learn about this in my role on the Human Venture Leadership board. Questioning assumptions about organizational structure has become a habit of thought that I frequently go back to and has prepared me to support other organizations in diagnosing and preventing challenges.

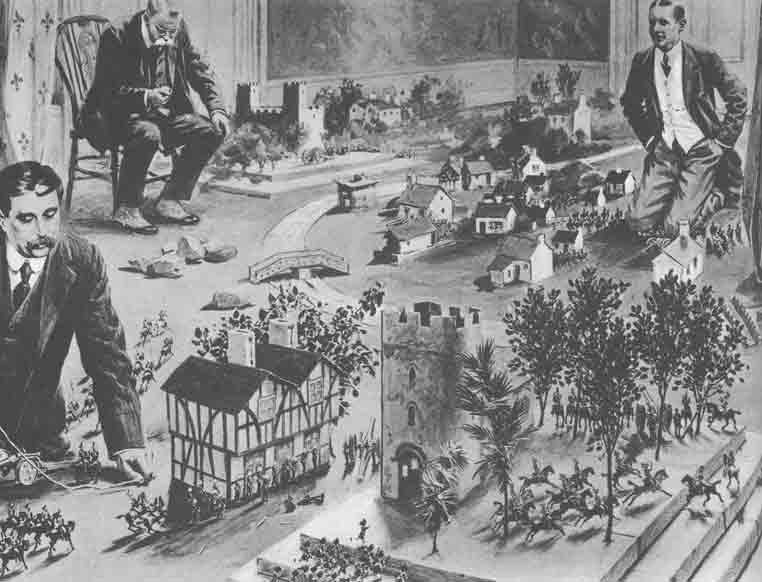

This may seem like a fairly mundane example but it instills habits that can trickle into all of our life engagements. H.G. Wells in The Open Conspiracy: What are we to do with our lives? writes: “Remaining in normal life we must yet keep our wills and thoughts aloof from normal life and fixed upon creative processes [adaptive learning]. However busied we may be, however challenged, we must yet save something of our best mental activity for self-examination and keep ourselves alert against the endless treacheries within that would trip us back into everydayism and disconnected responses to the stimuli of everyday life.”

H. G. Wells playing a wargame. A creative mind. Illustration first published in Illustrated London News (25 January 1913)

Striving & Discipline

Taking the adaptive path helps us to assess our routines and expand the kinds of habits we can build into our lives to support adaptive everydayism. We build more tools and techniques to draw on when we get stuck in a rut or are faced with a challenge. However taking the adaptive path is one thing, maintaining it is another.

Most of us have grown up in conventional learning environments which accustomed us to managing challenges that don’t take too much time or effort and have lots of pay off within that narrow context. For many of us, we often aren’t rewarded for moving beyond surface level understanding; we are rewarded for productivity and efficiency standards set by external authorities. For those working in management or specialized disciplines, we may be rewarded for deeper inquiry required for strategy, innovation and creativity but it is bounded by narrow institutional priorities.

This kind of thinking has eroded our capacities for adaptive discipline and striving, the core of adaptive learning. What the world needs most today, is for us to be learning beyond society’s current priorities and developing our capacities to tackle the emergent, complex challenges that face our world.

Striving is the process of matching our personal powers to life challenges. To design adaptive everydayism, we have to ask ourselves what life challenges are we preparing ourselves for? Are we caught up in developing our personal brand and marketing ourselves to our friends, work, and community or are we working to develop ourselves as human beings seeking to contribute meaningfully to this amazing phenomenon called humanity and life?

To bring this down to a practical level, it might be helpful to ask: What are you paying attention to? Why? What does it serve? A great example to dig into is the whirlwind of distractions of text chirps, facebook messages, pop-ups and everything else trying to capture our attention. Did you know that social media companies hire designers from the gaming industry who are masters at encouraging addictive behaviour? Furthermore, we are learning that these industries are serving to collect user data and sell it for marketing and political purposes. How should we be engaging in these platforms in more adaptive ways?

Social media is just one example, we all know there are plenty of sources of distraction. David Brooks, author of a New York Time article titled The Art of Focus says, “If you want to win the war for attention, don’t try to say ‘no’ to the trivial distractions you find on the information smorgasbord; try to say ‘yes’ to the subject that arouses a terrifying longing, and let the terrifying longing crowd out everything else.”

Paying attention to the potential for meaningful pursuits and making space in our lives to actually pursue them is part of the adaptive everydayism challenge. This is where discipline comes in. Discipline is the core of striving and it underlies the self-coaching capacity required to stick to the path you’ve started and push yourself beyond where you thought possible. It is important to remember that we often underestimate our own abilities and discipline can help us test our edges. Discipline is the process of detection and correction and/or anticipation and prevention of ignorance and error. In other words, it helps us identify blind spots and potential traps in our thinking. This takes work.

Cal Newport author of Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World, says “[The deep life] requires hard work and drastic changes to your habits. For many, there’s a comfort in the artificial busyness of rapid email messaging and social media posturing, while the deep life demands that you leave much of that behind, there’s also an uneasiness that surrounds any effort to produce the best things you’re capable of producing, as this forces you to confront the possibility that your best is not (yet) that good…But if you are willing to sidestep these comforts and fears, and instead struggle to deploy your mind to its fullest capacity to create things that matter then you’ll discover, as others have before you, that depth generates a life rich with productivity and meaning.”

Motivation & Self-Cultivation

Creating and sustaining adaptive everydayism is rare in our society. There are many ways in which we can go astray. We can have false starts where we set the intention, take a few steps then fall back to old habits. We can be faced with the reality of how hard it really is and lose motivation. We can get tired along the way and need to stop for rejuvenation. We can even start to tell ourselves this is as good as it gets. These are times when we need to mobilize our motivation in order to persist in our pursuits of adaptive everydayism.

Our motivation can be driven by a number of things, however they don’t all lead to adaptive striving. For example, we are often motivated by narrow self-interest and wanting to “get ahead in the world”. We can be motivated too by belonging and fitting in. Connecting with our human story and realizing that humanity can do better is one of the best motivations for building adaptive everydayism. Moments of inspiring human achievement or disastrous human failure remind us that we have responsibilities to the collective and to our fellow mankind. Paying attention to these stories helps integrate our daily habits into our larger world needs.

Humans have known this. Many cultures of the past have built concepts into their social structures to support his connection. Bildung is the German tradition of self-cultivation that refers to both personal and cultural development. It is a lifelong process of becoming that involves the development of an individual’s humanity and links one’s personal life journey with the deeper meaning of life.

Sociologist Tony Waters of the California State University said “Bildung, I discovered in my 2 years in Germany, is an organizing cultural principle for German higher education that trumps both careerism and disciplinary silos. It is generally translated as ‘education’, but in fact it means more—dictionary definitions often refer to ‘self-cultivation’, ‘philosophy’, ‘personal and cultural maturation’ and even ‘existentialism’. Bildung is the cry of the land, of poets and thinkers against the demands of credentialism, professionalism, careerism and the financial temptations dangled to graduating students.”

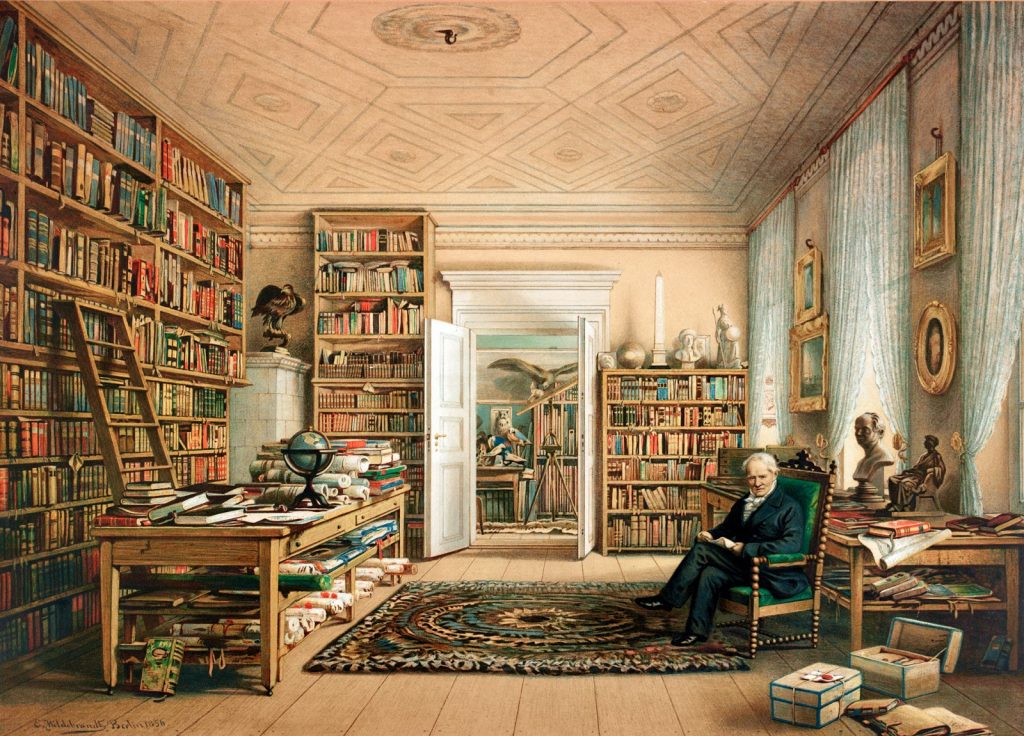

For an inspiring example of bildung, we can look to the seventeenth century Prussian naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humbolt whose amazing life travels through South America can be found in Andrea Wulf’s book The Invention of Nature: Alexander Humbolt’s New World. Interestingly, his brother Wilhelm von Humbolt explored similar concepts to bildung in his work as a philosophical and educational administrator.

In describing Von Humbolt’s circle of friends, which included the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Wulf writes, “During Humbolt’s visit, the men met every day. They made a lively group. There were noisy discussions and roaring laughter – frequently until late into the night. Despite his youth, Humbolt often took the lead. He ‘forced us’ into the natural science Goethe enthused, as they talked about zoology and volcanoes as well as about botany, chemistry and Galvanism. ‘In eight days of reading books, one couldn’t learn as much as what he gives you in an hour,’ Goethe said.” Von Humbolt clearly had a zest for discovering all he could about life and humanity as he trekked across the landscapes of Europe and South America and back into the salons of London, Paris and Berlin.

Alexander von Humboldt in his everydayism (Painting by Eduard Hildebrant, 1856)

Unfortunately, in our modern North American culture, we’re missing this concept and we have a lot of work to do to to cultivate it. We have to seek out things that light the fire in our bellies and help to light it in others. When you feel frustrated with the status quo and with seeing waste, suffering and injustice or next time you think “we can do better!”, know that it is from this that we can cultivate our motivation for adaptive everydayism.

We know from past examples of lives lived that creating adaptive everydayism is doable. There can be barriers, including our family or financial responsibilities, but creatively approached, this life can be an incredible adventure for you and those around you. As we redesign our priorities, others pay attention and wonder how they can too and this impact can have a ripple effect out into the boarder culture.

Our world needs people stepping in to this challenge and imaging new, meaningful ways of living. As Ken Low, curator of the Human Venture Meta Framework says, “Where there is a will there is a way is not always true, but there will never be a way without many wills.”

I end off, fully acknowledging that I have in no way mastered the advice I am giving. I am on a journey too. Sometimes I can successful get into new adaptive habits, sometimes I fall back on old ones but I am picking up new ways of being mindful of everydayism and finding new tools to flip it on its head.

I know that I need ongoing reminders to keep me engaged in meaningful pursuits. I am constantly finding these reminders in the Human Venture community and in the two communities we all belong to: humanity and life. Lately, as the spring bird migrations are starting, I am finding my everydayism influenced more and more in building habits of observation. From my desk, I can see returning species coming to the feeder and I am reminded of the larger rhythms of life going on around us. It reminds my that my life rhythms change too.

I hope this is a reminder for you. With patience and persistence, soon adaptive everydayism becomes everymonthism, everyyearism and eventually your everylifeism.

More Resources:

The Open Conspiracy: What are we to do with our lives? by H.G. Wells

The Art of Focus, New York Times Article by David Brooks

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport

The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humbolt’s New World by Andrea Wulf

Wikipedia Bildung – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bildung

Waters, Tony (2015). “Teach Like You Do in America–Personal Reflections about Teaching in Tanzania and Germany,” Palgrave Communications (2015) http://www.palgrave-journals.com/articles/palcomms201526

The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in the Age of Distraction by Matthew Crawford

The Oxford Handbook of Lifelong Learning

The Art of Living: The Classic Manual on Virtue, Happiness and Effectiveness by Epictetus

HV Meta Framework Map 36 The Process of Discipline

HV Meta Framework Map 36.1 Notes on Discipline

HV Meta Framework Map 20: Adaptive Learning & Control – First Step

HV Meta Framework Map 100: Adaptive Persistence

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to members of the Human Venture learning community including Ken Low, Elizabeth Dozois, Sami Berger, Natalie Muyres, Harold Semenuk, Laura Kennett, Chris Hsiung, and Blythe Butler for sharing your ideas and for reviewing this article.

Feature Photo by rawpixel.com on Unsplash