Photo by Markus Winkler on Pexels

A Disciplined Inquiry of AI

Since the first article in this series was published in May 2024, there have been several significant advancements in artificial intelligence* (AI), and we are witnessing an increasingly public race between nations like the United States and China to be the global leader. AI seems to be popping up in every aspect of my life and professional network with increased (and slightly annoying) frequency.

My intent for this AI inquiry was to ponder an AI future. What does it mean for me personally? For my work? For life and humanity? What lessons from history can we draw on to design a safe and trustworthy path forward? What do individuals, governments, and society need to do, and how do we prepare for an AI future?

After more than a year of inquiry that involved exploring a diverse collection of AI thinking, I find myself in the middle of an AI spectrum. At one end of the spectrum there is a utopian future where AI eliminates some disease and frees up humans to focus on more strategic or meaningful work. At the other end is a dystopian future, where AI diverts humanity to near extinction. I see exciting but also concerning possibilities that require an abundance of caution.

Today, I am asking what does a responsible AI future look like and what is required to achieve this? Personally, I want to equip myself to make decisions and choices to use AI responsibly, for myself, my clients, and future generations. I also want to be aware of and track the socio-cultural impacts of AI, identifying what to pay attention to and not be naïve to harmful developments shrouded in hype.

I sifted through and explored a plethora of resources including books, podcasts, news articles, and blogs written by AI pioneers, critics, and investigative journalists. I’ve curated an evolving resource list to support your own exploration of the concerns and possibilities of an AI future.

Learning from History

I spent the first part of my career working in aviation, including emergency management. The institutions, standards, and governance that make aviation safe are an obvious model to safely progress AI. In the first article in this series, I pointed to the need for a preventative and proactive approach to AI development – learning from history and considering an AI that benefits all of life and humanity. I pointed out how safe commercial aviation is due to their disciplined commitment to anticipate and prevent a multitude of harmful scenarios. Since humans took flight, aviation has learned, established, and maintained international regulations and oversight for safe operations and a sustained industry.

When I was an emergency management leader, the most impressive aspect of accident prevention was the degree to which the global aviation community transparently shared safety lessons. Whether a near miss or mass fatality accident, root cause and lessons are shared across the global industry. Commercial airlines may compete for passengers, but they don’t compete against each other on safety. Nobody would get on an airplane with that degree of uncertainty.

In the second article, I explored the concept of intelligence and proposed the need for systemic adaptive intelligence for designing and deploying artificial intelligence for the benefit of humanity. “Systemic adaptive intelligence seeks to understand the current situation, the history and past causal factors, and possible scenarios into the future. This form of intelligence strives to ensure that our knowledge and information closely matches what is actually going on and continually tests and questions facts and stories to confirm they correspond with reality – essentially, that the map matches the terrain” (Muyres 2024).

Imagine a world where a “trial-and-error” approach to safety engineering was acceptable (Tegmark 2017). Or airline safety was left up to the person on duty and their own ideas of how an airplane is designed and maintained. If this sort of oversight was acceptable, I surmise there would not be much of an aviation industry. Those who travelled would knowingly roll the dice on their lives each time they flew. The good news is this is not the case. When the risks are high and consequences severe, we require disciplines and oversight that transcend those of our own beliefs and standards. And when the disciplines are in place to protect and enable humanity and life to flourish – this is systemic adaptive intelligence. If a degree of systemic adaptive intelligence can be achieved in aviation, I have confidence it can be applied to the realm of AI.

“Nobody would want to fly in a Boeing 737 Max after its two crashes and scary door plug incident without a thorough investigation, and nobody should imagine that AI – perhaps the most powerful and hence potentially new technology of our time-should be magically exempt from regulation. It’s absurd not to regulate it.”

Marcus 2024

Systemic Adaptive or “Meta” Oversight and Control

Oversight and control can be described as the rules, checks, and balances in place to prevent and correct negligence, error, and failure in systems and processes. For instance, financial and food production systems are governed by the oversight bodies of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

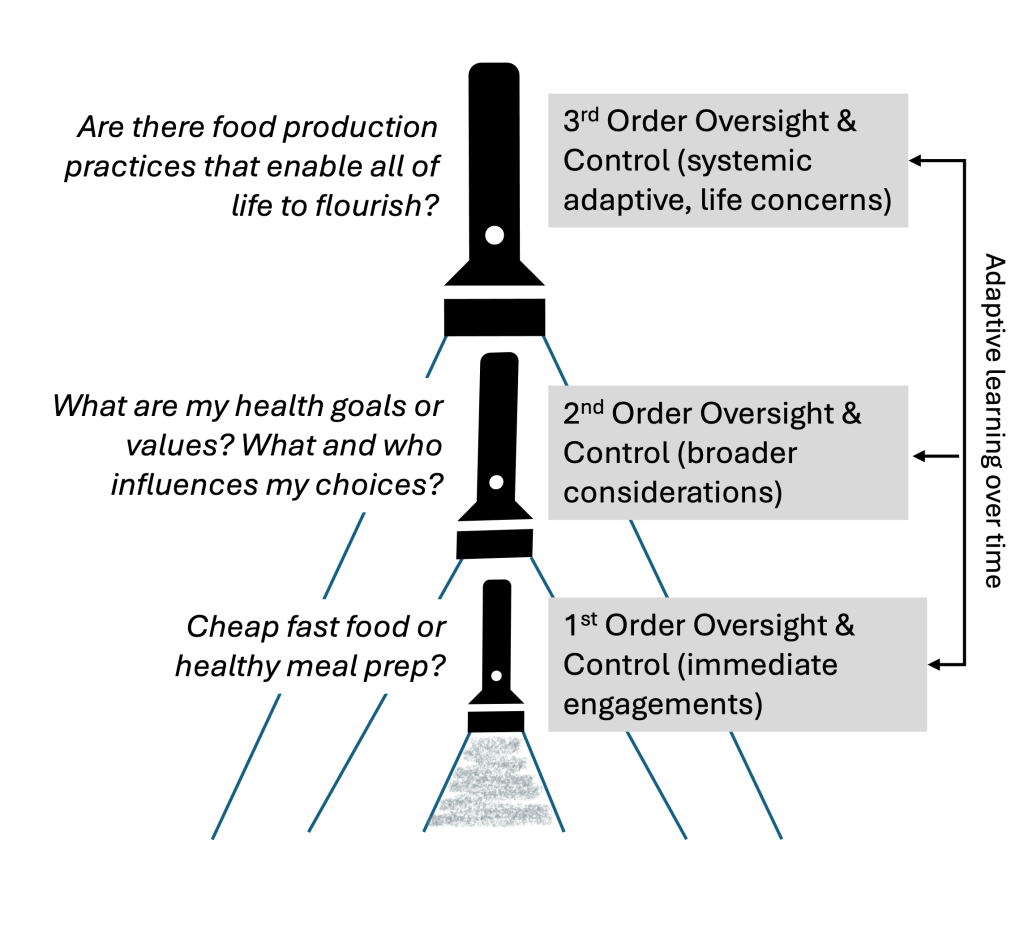

At the Human Venture Institute, we consider three orders of oversight and control. Think of a stacked set of three flashlights. Each flashlight represents the span of where we must cast our attention to be most helpful – each level increasing the scope of what must be considered to avoid failure and harm. The three orders are applicable to individuals, groups, institutions, and society.

The first or lowest flashlight represents an operational level or order of oversight and control. For individuals, this 1st order guides our immediate engagements, like whether to purchase a fast-food meal or whole foods to cook a healthy meal. In aviation, these are the decisions made by pilots during flight using flight indicators as a guide. The 1st order is what we pay attention to in the immediate situation.

The second order of oversight and control, represented by the middle flashlight, ensures the immediate engagements fit with broader goals, values, and responsibilities – some well-constructed, some not. As individuals we may value wellbeing and monitor our health by weighing ourselves, monitoring our heart rate, and annual medical exams. In aviation, there is a network of oversight mechanisms overseeing the safe operation and maintenance of aircraft and global flight paths. A breakdown in these oversight mechanisms can be harmful and even catastrophic.

Our individual 2nd order of oversight and control is formed through a combination of our biological drivers, our accumulated experiences and learning over time, and socio-cultural influences like media, marketing, politics, education, religion, and community allegiances. This second order is not static and can change, resulting in different first order choices. If eating fast-food is causing high cholesterol, inconsistent with your values for health and wellbeing, you may shift your choices and prioritize healthy food. Historically, aviation accident investigations led to adjusting standards and oversight mechanisms to ensure a safe and sustainable industry.

Our challenge today is that much of the social-cultural influences guiding our thoughts and actions at the 1st and 2nd levels of oversight and control are resulting in devastating consequences for our species and planet. For instance, unfettered capitalism and consumption values result in factory farming and monoculture crops putting the food systems we depend on and our health at risk. We need a higher level of oversight, or “meta” oversight, that supports wise action to prevent disaster, course correct, and design better ways of living on this planet. This meta level of oversight is the top flashlight, the 3rd level of oversight and control or systemic adaptive oversight and control. In the case of food production systems and institutions, we must extend the scope of consideration beyond the corporate bottomline to that of life and humanity. Oversight mechanisms at a systemic adaptive level would consider what is best for all of life to flourish, not just shareholders and fulfilling short-term financial and food production goals. The 3rd order of oversight and control is the frontier of human and social development.

There are many individuals and organizations we can draw on to understand how 3rd order oversight and control can be developed but we have yet to achieve this on a systemic scale. Regenerative agriculture is building capacities for 3rd order oversight at a grassroots level and efforts are being made to translate this into systemic adoption. However, given the forces of the existing system we have yet to see if this will be successful.

“This isn’t just about the technology itself; it’s about how we choose to shape and deploy it. These aren’t questions that AI developers alone can or should answer. They’re questions that demand attention from organizational leaders who will need to navigate this transition, from employees whose work lives may transform, and from stakeholders whose futures may depend on these decisions. The flood of intelligence that may be coming isn’t inherently good or bad – but how we prepare for it, how we adapt to it, and most importantly, how we choose to use it, will determine whether it becomes a force for progress or disruption.”

Mollick 2025

A Responsible AI Future

The three levels of oversight and control can be applied to artificial intelligence. In the immediate situation, AI is used for a variety of reasons, some adaptive like analyzing radiological images for early detection of cancer. This application of AI is driven by an intent to improve the lives of humans and the oversight is provided by medical governing bodies who ensure safe application of new drugs and medical interventions. Most people would not turn over their health to technology without some level of assurance the advice was helpful and not harmful.

However, the general adoption of AI in all aspects of our lives, like reading and responding to emails and conducting research, is being increasingly challenged for possible societal implications, increased energy consumption, and lack of sound business cases or return on investment. Organizations globally are jumping on the AI wagon and paying an enormous amount of money to replace workers with AI tools, but the jury is still out whether these are sound business decisions (Bloomberg 2025; Goldman Sachs 2024).

Recent studies are also reporting concerning trends of dependence on AI tools for cognitive tasks like writing and information synthesis. This cognitive offloading in our work and in children’s education systems may result in the deterioration of critical thinking skills (Gerlich 2025; Lee et al. 2025). Relying on AI tools while deteriorating our critical thinking skills could lead to an overreliance on chatbots to make choices for us and telling us what to think and how to act.

“Governing generative AI models for the common good will require mutually beneficial partnerships, oriented around shared goals and the creation of public, rather than only private, value.”

Mazzucato 2024

Systemic Adaptive or “Meta” Oversight of AI

The need for higher levels of oversight and control for the safe development, commercialization, and use of AI is clear. Today the degree of oversight is limited to laws and governance established for technology and actors in an internet enabled world and are far from governing an AI enabled world. The headlines increasingly report deep fakes, fraud, and disturbing uses of the internet and AI for exploitation and abuse.

As computer scientist and leading AI researcher Stuart Russell (2020) points out, there are a number of promising initiatives underway by corporations, academic institutions, and governments to establish AI regulation but practical implementation is constrained by corporations who desire to maintain control over AI systems. Today, the AI industry is driven by first to market and profitability and does not have enough public pressure or concern to incentivize collective and global safety regulation akin to something like aviation or nuclear energy. This needs to change.

Government policy makers (and AI corporations and developers without provocation) could take a page from aviation and mandate a small investment, even 1% of total research and development dollars, to be allocated toward oversight and safety. This would provide the initial measures of oversight and recognize our current AI governance structures are not equipped for the technological acceleration in progress. Safety policies as demonstrated by the aviation industry provide a benchmark for “global collective problem-solving” that protects humanity (Javorsky 2024).

“I have no doubt that the transition from an unregulated world to a regulated world will be a painful one. Let’s hope it doesn’t require a Chernobyl-sized disaster or worse to overcome the industries’ resistance.”

Russell 2020

Systemic adaptive oversight of AI would enable and sustain a global collective and third party governance structure to design, develop, and commercialize AI aligned with the needs of humanity and life on earth. This sort of oversight requires individuals, governments, and organizations to question their intentions and measure them against what is best for all of life and humanity – not just the bottom line or to beat their competitors (including other nations) to market. That is the AI future I want to live and work in: a future where I can be certain bad actors and adversaries are restricted from taking advantage of my thinking, caring, and acting and designed by individuals and organizations that care about our collective flourishing.

“We therefore need to build institutions that will be able to check not just familiar human weaknesses like greed and hatred but also radically alien errors. There’s no technological solution to this problem. It is, rather, a political challenge. Do we have the political will to deal with it?”

Harari 2024

*I have personally become increasingly knowledgeable about artificial intelligence and this includes what marketing and media would like us to think AI is. For the purposes of this article, I am using “AI” generally and to describe the many forms of AI-like technology being used and marketed today. I have purposefully not included a detailed description of the types of AI, what AI isn’t, or how these technologies are being used. The resources provided in the 2024 Artificial Intelligence Resource List are a good starting point to explore this.

Resources cited in this article:

- Bender, Emily M. and Alex Hanna. 2025. “The AI Con: How to Fight Big Tech’s Hype and Create the Future we Want.” Harper Collins.

- Bloomberg. 2025. “Klarna Slows AI-Driven Job Cuts with Call for Real People.” Bloomberg, May 8, 2025.

- Gerlich, Michael. 2025. “AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking.” In Societies, 2025 15(1), 6.

- Goldman Sachs. 2024. “Gen AI: Too Much Spend, Too Little Benefit?” Global Macro Research, June 25. 2024.

- Harari, Yuval Noah. 2024. “Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI.” Penguin Random House.

- “Emilia Javorsky on how AI Concentrates Power” on Future of Life Institute podcast, July 11, 2024.

- Lee, et al. 2025. “The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers.” In CHI’25: Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, No.: 1121 (1-22).

- Marcus, Gary. 2024. “Taming Silicon Valley.” The MIT Press.

- Mazzucato, Mariana. 2024. “Government’s Must Shape AI’s Future” in Project Syndicate.

- Meng, Xiao-Li. 2023. “Data Science and Engineering With Human in the Loop, Behind the Loop, and Above the Loop.” Harvard Data Science Review, 2023, 5(2).

- Mollick, Ethan. 2025. “Prophecies of the Flood.” Substack.

- Muyres, Natalie. 2024. “Mapping the AI Territory – Intelligence.”

- Russell, Stuart. 2020. “Human Capable, Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control.” Penguin Random House.

- Tegmark, Max. 2017. “Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence.” Alfred A. Knopf.

- “The Human Venture & Pioneer Leadership Journey Reference Maps” by Action Studies Institute. Calgary, Alberta, 2019.

Although I have created a great list of resources for an inquiry into artificial intelligence, it will remain incomplete. I have updated the 2024 Artificial Intelligence Resource List with additional resources, but this list will no longer be updated going forward.

Natalie Muyres is a Human Venture Leadership Associate and current Co-chair of the Human Venture Institute. She is an independent applied organizational and design anthropologist, consultant, project manager, and organizational change management professional in Calgary, Alberta.

Human Venture Leadership is a non-profit learning organization, providing proven educational programs that enable and grow the leadership capacities of individuals, communities and our global society. The Human Venture Institute is a research hub whose primary function is to cement and extend Human Learning Ecology.