Memory is a critically important part of adaptive intelligence. The function of memory is to record and store relevant aspects of experience and observation, providing the material out of which we construct the lessons that guide our actions and further learning. Some lessons come almost automatically, like not touching a hot stove, some require a mentor or instructor, and others we have to work out on our own. The adaptive value of lessons depends on a combination of the quality, relevance and comprehensiveness of the memory and our motivation and ability to find meaning in it. Experience, memory and learning processes are complex and vulnerable to many influences that can misdirect or limit the value of any lessons they generate.

Experience, memory and learning processes are more complex when societal scale endeavours are involved. Societal scale endeavours include all the basic functions of civil society including: government, education, public health, environmental protection, justice systems, economic development, emergency services and disaster management, security and war fighting. Societal scale endeavors are carried out by specialists, embedded in large, hierarchically structured institutions. Most of the population will have limited roles and experience, and most of those who are directly involved will be engaged in operations at different levels. The experience, memories and lessons learned will be different, but most societal fields of endeavor are ongoing and don’t require a willingness to sacrifice one’s life – or to give orders that will cost the lives of subordinates.

War fighting is a unique societal scale endeavour. It is a mixed bag of courage, survival, self-sacrifice, existential bonding, waste, suffering, strategic foresight, brilliance, and monumental incompetence. All wars are contests of adaptive learning requiring a capacity for rapid, real-time adaptation, which means that the character of the war changes as the war progresses. For instance, at the outset of war in 1914, the British and French armies had less than a few hundred machine guns between them. The guns were heavy and unreliable. They had been used extensively to subjugate and control tribal peoples of Africa, but the professional military viewed them as improper weapons to be used against white Europeans. Germany had no such reservations and had 12,000 efficient and reliable Maxim machine guns in 1914, a number that grew to 100,000 by war’s end.

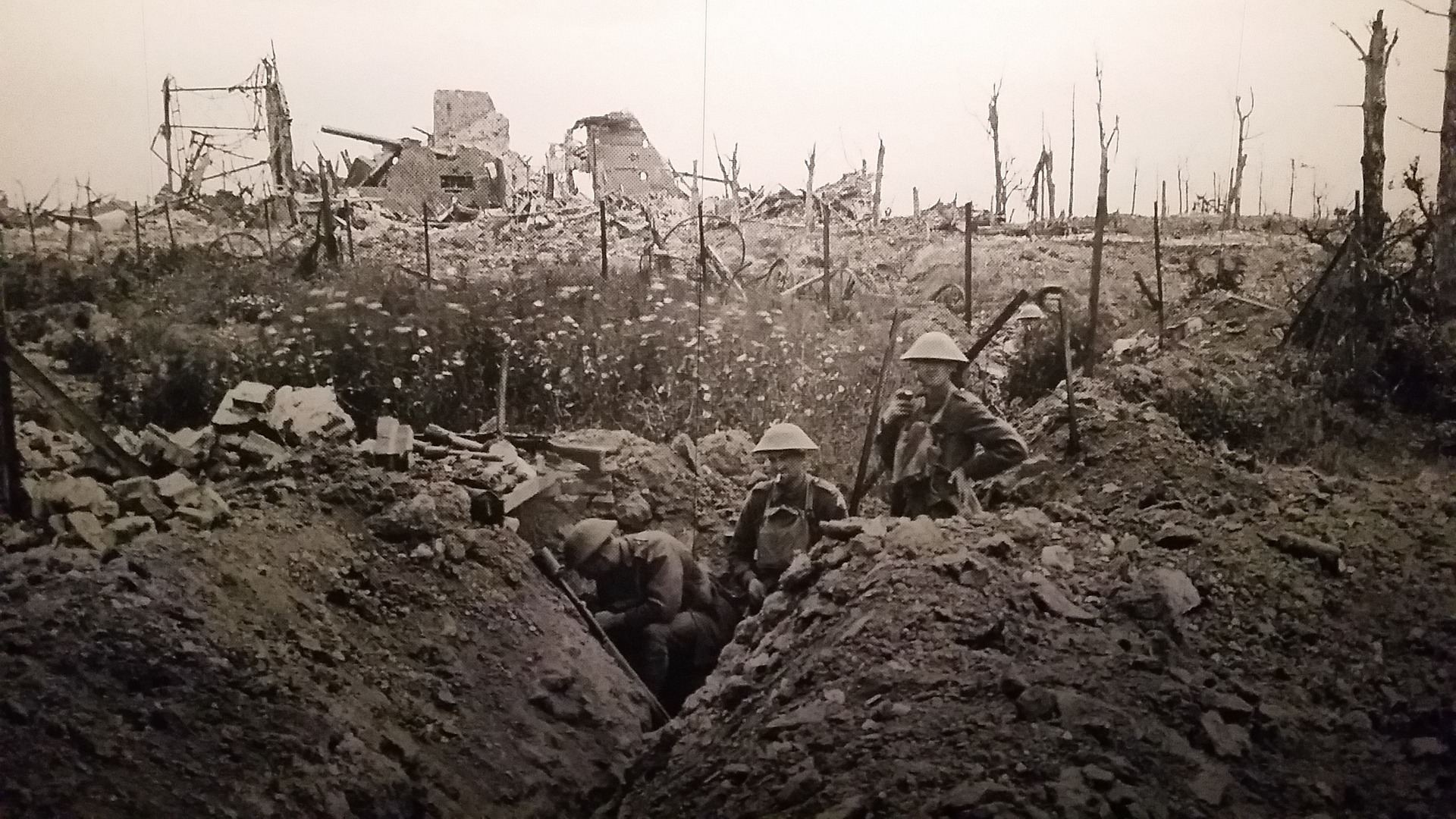

The combatants found to their repeated cost the futility of massed infantry attacks against well-entrenched defensive positions protected by machine gun cover. The first day of the Somme offensive clearly illustrated this, although the lesson appeared to be lost to the British high command. On the opening day of the offensive, the British suffered a record number of single day casualties – 60,000 – with the great majority lost under withering machine gun fire. Hundreds of thousands of young men died because tactics and strategy didn’t keep pace with technological development – a pattern we see repeated in different fields of endeavour.

At the outset of the war in 1914, people expected it to be finished fairly quickly and there was widespread enthusiasm on all sides to engage in war. Based on the history and lore of recent European wars, people generally expected the war to be short and something of an adventure, where courage, pluck, determination and national spirit would win the day. No one anticipated the grinding, muddy slaughter that unfolded. The war created a kind of existential shock that rippled through the 20thcentury and is still reverberating today.

One hundred years ago, after 4 years of brutal conflict, the “Great War” finally came to an end. Leaders of the opposing forces met at 5am in a railway carriage in the Forest of Compiegne, France on November 11, 1918 to sign the Armistice that would take effect six hours later – the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

The first Armistice Day was conducted in 1919 in ceremonies throughout Britain and the Commonwealth. It commemorated the end of the war the previous year and helped establish a shared sense of grief, loss and gratitude. After the end of the Second World War in 1945, Armistice Day became Remembrance Day to include all those who had fallen in the two World Wars. In Canada it now includes all the wars, conflicts and peace keeping operations.

Remembrance Day can produce conflicting emotions. While the ceremonies are moving, and appreciation of veterans is heartfelt, it can also seem that something is missing. If we are genuinely concerned about the sacrifice of veterans, wouldn’t it make sense to look into the causes of war and ways to prevent it? Memorial ceremonies are not a viable format for that level of historical inquiry, but today in addition to the ceremonies and formal gatherings we have a wealth of resources to draw on. One cannot remember something that wasn’t known in the first place. Memory begins with learning.

Remembrance Day 2018 is the time to start preparing for Remembrance Day 2019. Keep in mind that at a societal level the understanding of war, given its scope and complexity, has to be multifaceted and multi-levelled. Learn as much as you can about what the experience of war means to others. Your own understanding will grow and become more comprehensive as you do so. Expect to have to search and dig to find resources that touch on the causes of conflict, strategy and adaptive learning.

On the other side of memory we are looking for the lessons memory can teach. What’s relevant today? What should concern us about current events and given what we know about the causes of war?

Here’s a few recommendations to get you started:

- “Tribalism: The Evolutionary Origins of Fear Politics” by Stevan Hobfoll; Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2018 edition (July 26 2018)

- “What the Thunder Said: Reflections of a Canadian Officer in Kandahar” by Lieutenant- Colonel John Conrad; Dundurn; 2009

- “Among the Walking Wounded: Soldiers, Survival and PTSD” by Lieutenant- Colonel John Conrad; Dundurn; 2017

- “D Day 360 You Tube” PBS documentary

- “Hyena Road” Canadian war movie directed by Paul Gross

- “Band of Brothers” series

- “Samurai: the autobiography of Japan’s World War Two Flying Ace” CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015 [first published in 1957]