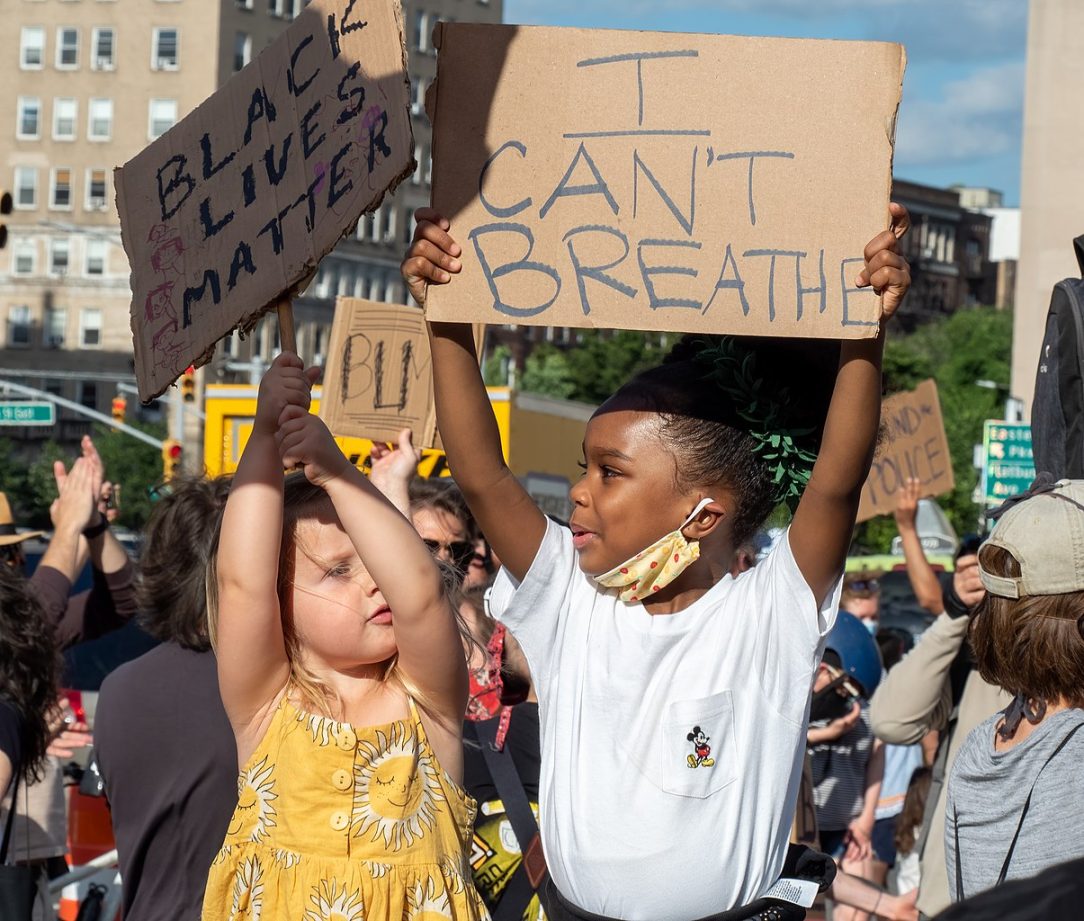

George Floyd protest in Grand Army Plaza June 7, 2020. Image: Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Laura Kennett

I wrote Part 1 of this article, Systems in Converging Crisis, in the spring, when I listed an array of crises that are intensifying around us, including:

- Global COVID-19 pandemic,

- Global climate change,

- Global oil market collapse,

- Global fracturing of truth in social media, and

- Global rise in right-wing movements.

Now we have entered summer in the northern hemisphere and this list is already obsolete. I need to add the explosive response to the killing of George Floyd which served to highlight the long and ongoing history of destruction and re-configuration of Black communities and abusive practices by police and other social services. The collective ‘we’, especially people of white privilege, failed for too long to take anticipatory action to ensure all human lives are treated with dignity and respect. It’s disappointing, but not surprising, that it took the circulation of vivid footage of another Black man losing his life at the hands of a police officer to expose the injustices in a manner that a wider range of people could emotionally align with.

What is fascinating with these crises is how each exacerbates the others because they are all systemically linked. Like a game of rock-paper-scissors, each crisis has an effect on the others: Right-wing movements reduce action on climate change; climate change stresses vulnerable populations and economic markets; stressed markets and anxious populations contribute to tribalism, bias and misinformation in social media; fractured truth in social media inflames mistrust of police and politicians and stirs up unreconciled anger in response to ongoing systemic discrimination; public gatherings of people protesting systemic discrimination leads to superspreading pandemic events; pandemic events stress economic markets; and so on…

We don’t like crisis. Crisis creates anxiety and sends fear through our bodies. Even without an actual virus in our body, emotions can make us ill. The antidote we grasp for is security, stability, power, and control, and we grapple for information and narratives that make us feel oriented amid a crisis. Our human nature wants to put awful feelings at bay as soon as possible. But watch out, for here lies a trap.

Naomi Klein’s book, Shock Doctrine, defines shock as “a moment when there is a gap between fast-moving events and the information that exists to explain them.” And it is during these transitory moments when individuals and organizations with a clear but potentially harmful agenda, will use their strength, capacity and resources to take advantage of vulnerable groups by offering narratives that create the façade of security and comfort – a trap! Klein’s book illustrates the structure of this trap: “As soon as we have a new narrative that offers a perspective on the shocking events, we become reoriented and the world begins to make sense once again.”1 However, we must recognize that emotions can drive us to latch onto narratives that give short term relief, often at the expense of adopting narratives that are unreliable, inaccurate, and orientated to unhelpful frames of action and thinking. This is a pattern that leaves us vulnerable to further impacts from a complex interaction of crises.

With multiple crises stacked on one another and exacerbating each other in ways that we do not fully understand, now more than ever we must stretch our capacity to find narratives that are helpful in the context of inter-generational survival of our species and life on this planet, even if these new narratives do not bring immediate comfort.

Throughout history, humans have been very resilient and have managed through previous pandemics, wars, riots, and economic depressions. When we look at how humans built resiliency and navigated through past crises, we can see a common pattern of activities: Scrambling to identify and establish sources of intelligence to help identify potential courses of action and probable outcomes of those actions. What is ultimately important is having the discipline to sift through noise and seek out reliable and accurate sources of intelligence while continually testing how those sources match actual observations. In the study of human learning ecology, this approach is a component of “adaptive controls” and essential to achieving the ultimate goal of all living systems: survival.

In summary, in the initial disoriented state of a crisis, we clamber for new and reliable stories because we yearn for security. But we tend to latch onto early sources of information, regardless of their quality, because they are the shortest path to making us feel secure and comfortable. At the Human Venture Institute, we refer to this process as Level 1 learning – learning that is largely dictated by our biosocial drivers. Our reptilian brain makes us freak out and react to the frenzied messages on social media to hoard toilet paper and yeast. Does this mean humans have a design flaw?

Alas, we are not completely flawed. We do have capabilities for re-constructing how we learn to manage the challenges around us. We can learn to recognize that fear is an important, natural, and uncomfortable signal that there may be a threat and we can learn to override reflexive, maladaptive responses to fear. However, the even bigger crisis that looms large and infiltrates human society is that most humans are not supported by a culture that cultivates the capacities and disciplines required for people to engage in a helpful pattern of sensing-and-adaptive-responses. Through the continued practice of disciplined inquiry and testing in support of the progress of life, we can work together to develop the oversight and control that uses fear and discomfort as indicators that it’s time to dedicate energy to figuring out how adaptively learn to adapt to the ever-morphing challenges of converging crises.

We don’t need another crisis to realize we need to do more to co-develop our systemic adaptive learning capacities – We have more than enough crises to get started.

1 Klein, N. (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Toronto, Canada: Vintage Canada, p. 552.

Laura is a Human Venture Leadership Alumnus and a Human Venture Leadership Board Member. Laura is currently the Director, Technology & Information Business Services for Liquids Pipelines at Enbridge.